On this date Sheriff William

Hoggatt summoned a jury of neighbors to meet him where the Vincennes Road

forded Blue River downstream from where Mill Creek flowed into it. Sheriff Hoggatt was acting under a writ

issued by the Washington Circuit Court. George Beck had appeared before the

Washington Circuit court on in late November 1814 seeking the issuance of a

writ of ad quod damnum so that he determine whether to build a milldam on Blue

River in the southeast quarter of Section 11, T1N, R3E. Beck had obtained title to this land from the

US Government on February 23, 1813. Beck’s

Mill was located in the diagonally adjoining northwest quarter of Section 11,

T1N, R3E. It was at this location in

1808 where George Beck and his sons had dammed the mouth of a cave spring that

had its outflow into Mill Creek. Mill

Creek took its name after Beck’s Mill which was about 2000 feet west of the

site where George Beck was considering building another mill.

“Ad quod damnum” is a Latin

phrase meaning “to what damage”’ It refers to a legal procedure where the sheriff inquires of jurors under oath as to

what damage a grant conferred by government would cause to various people if

the government were to make the grant. It can best be described today as a

private condemnation action. As many watercourses were either on unclaimed

public land or on streams declared to be navigable, the local court was vested

with the authority to control the use of rivers and streams. As the damming of a river would both reduce

the downstream flow and partially flood the river upstream, the value and use

of riparian land by both the US government and landowning neighbors could be

adversely affected. By the assessment of

damages by a jury, the proposing mill operator could determine if he wished to

proceed with the construction of the dam. The downstream owners below

Beck’s proposed milldam were the estate of Susannah Elliot and John

Sheets. The upstream owner with a

potential claim was Jacob Copple.

On the day that John

McPheeters received the verdict on the second slander suit he was litigating,

he hired attorney William Hendricks to obtain a writ of ad quod damnum from the

Washington Circuit Court so that he could construct a milldam on Lost River. Sheriff Hoggatt summoned a jury to assemble

at Lost River on December 3, 1814. The

McPheeters tract was described as the northwest quarter of Section 21, T2N,

R2E. This land today is bounded by Ike

Drew Road on the south; Roger Green Road on the north and the Orange/Washington

County line on the west. Interestingly,

McPheeters was seeking permission to build the milldam before he actually owned

this riparian land along Lost River.

Although he had undoubtedly registered his claim for this tract of land,

McPheeters did not actually make his payment in full until later which resulted

in his deed from the US Government dated April 2, 1818. Upstream occupants with

registered land claims from the McPheeters proposed mill site were George

Arnold and Harvey Finley. The downstream

owner was the trustee of the School Section as Section 16 in each congressional

township was reserved by the Northwest Ordinance to support public

schools. This land was leased by the

agent appointed by the provisional circuit court. David McKinney who had received his land

title on October 1, 1814 was the next downstream owner.

The records of the Washington

Circuit Court do not record what damage assessments these two juries

determined. As there was no operating

watermill in this part of Lost River Township, McPheeters must have thought

that he could get business in this area under settlement that was presently

going to Beck’s Mill on Mill Creek and to Samuel Lindleys Mill near Half Moon

Spring near Lick Creek. There is no record that a milldam was ever built by

John McPheeters or anyone else on Lost River in Washington County, Indiana

Territory.

The reason that George Beck

was interested in building a milldam on Blue River within shouting distance of

his well-known mill is unclear. Maybe

his first mill had so much business that he hoped to draw even more milling

work by having a nearby mill to accommodate the demand for ground grain on the

Washington County frontier. Beck did not

build a mill on his land on Blue River but, a flour mill was built about 1820 near

this location and was operated by Green and then by William Rudder for over 60

years.

The legal procedure used by

George Beck and John McPheeters in the late autumn of 1814 was seldom used by

other settler/entrepreneurs who built dams for the operation of either grist or

saw mills. Mills built by William

Lindley at three locations on Royse’s Fork of Blue River between Brock Creek

and the Middle Fork of Blue River did not use formal legal procedures to have

riparian rights declared. These dams may

have been built before there was a local court conveniently located to deal

with riparian property rights. The

milldam builders may have informally made arrangements with upstream and

downstream owners. These informal

agreements could have been compensated by free or discounted use of grinding or

sawing services at the mill.

Disputes over the use of

rivers and streams for milldams did arise in the early years of Washington

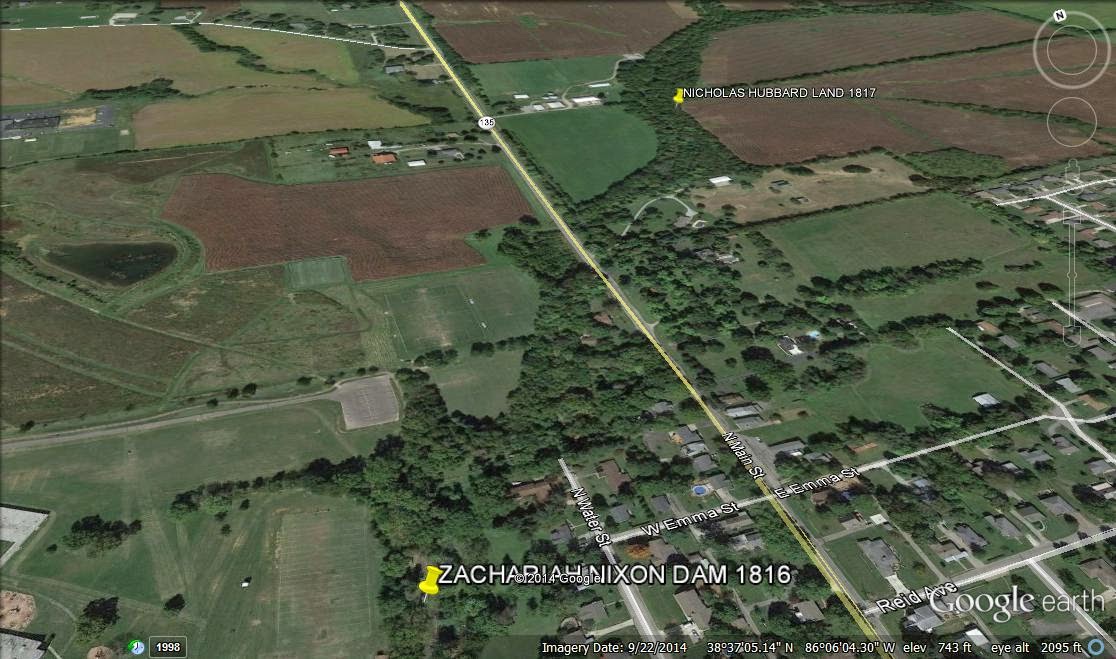

County, Indiana. In 1816, Zachariah

Nixon built a milldam on Brock Creek downstream from the present day location

of the Salem High School soccer field without using any legal procedure. Nicholas Hubbard who lived upstream from the current

site of the North Main Street Bridge took exception to Nixon’s dam claiming that

his land was damaged by the impounded water.

Hubbard and Nixon entered into a written agreement to choose four

arbitrators to assess any damages that were caused to Hubbard. Nixon also agreed to post a $100 bond to

guarantee payment of any damage award the arbitrators declared. The costs of the proceeding were to be

divided equally. The agreement was witnessed by Justice of the Peace John

McCullough and Jacob Smith on May 23, 1817.

The arbitrators selected were Godlove Kamp, William Lindley, Lewis Crow

and Jeremiah Lamb. These referees viewed the Nixon dam and the Hubbard property

and determined Hubbard’s damages to be $90.

The finding was filed with Justice of the Peace McCullough who then

ordered Nixon to pay the damages every six months in three installments of $30

each.

The result of the

Nixon-Hubbard dispute is somewhat puzzling as George Brock owned land between

the Nixon dam and the Hubbard land.

Looking at Brock Creek today, it is difficult to believe that a dam by

the football practice fields would impound water beyond the bend in Brock Creek

upstream from the SR 135 Bridge. Also the damage award seems rather generous as

George Brock and Nicholas Hubbard only paid $320 for the 160 acres that Hubbard

was protecting from impounded water.

Undoubtedly, early settlers highly valued having access to a free

flowing stream. Perhaps, this is why

John McPheeters who had a successful mill on the Mutton Fork of Blue River never

built a second milldam on Lost River.

GEORGE BECK'S MILL AND MILLDAM ON BLUE RIVER

PROPOSED MILLDAM OF MCPHEETERS ON LOST RIVER

NIXON DAM AND HUBBARD LAND

ON BROCK CREEK

No comments:

Post a Comment